EKŌ Temple

Traditional Japanese House

The walls are thin space-fillers, slidable and removable. The Tatami-mats, as well as the tokonoma, the display alcove, are not added after the event, like furniture or items for display, but instead belong to the body of the house itself. In this type of construction, structure and decoration are not separate or distinct: no empty box is built, and then filled.

The relation between house garden and architecture is a symbiotic one. The character for “garden” is made up of three elements: an outer wall, the main building-complex within, and the planted grounds, which in turn may have other structures. Whereas inside the house right angles dominate, with crooked or curved lines nowhere to be found, the plant and landscape zones, which can be regarded at leisure from the house, are ruled by a kind of controlled wildness, free of any suggestion of axial symmetry. Because its walls are slidable, the view from within the house of the garden, designed to be free of all regularity, can be “framed” in various ways: one time to appear as a long cross-section, another as a large hanging scroll landscape painting. Nevertheless, the paving stones leading out of the house demonstrate that the gardens here are not only “position”, but also “movement” gardens, the view of which changes in some specific way with almost every step.

Gardens

Temple Garden

Opposite the Mountain Gate, on the other side of the garden, on a boulder under a pavilion, stands a statue of Prince Shōtoku (Shōtoku Taishi, 574-622), donated to the EKŌ Center in 2002 by the prominent contemporary sculpter NAGAOKA Wakei. It was in the reign of Shōtoku that Buddhism came to Japan, and he made major contributions to its becoming widespread there.

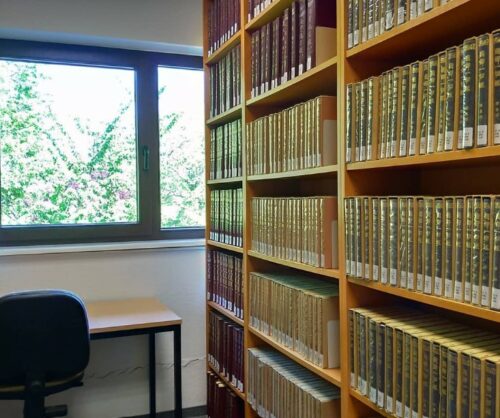

Library

Contact

Jan Marc Nottelmann-Feil

☎ 0211-577918-224

📠 0211-577918-219

✉ bibliothek AT eko-haus.de

Facilities

Main building

EKŌ Hall:

- exhibitions, concerts, courses, seminars, symposiums, lectures, etc.

Three seminar rooms (combinable):

- Courses, seminars, workshops, etc.

Exhibition foyer:

- Exhibitions

Kyōsei-kan (annex building)

Kyōsei Hall:

- exhibitions, concerts, courses, lectures, etc.